I always thought I had a good handle on gin. There didn’t seem to be that many different varieties; I felt like I knew the major players. It wasn’t until I started researching that I realized how much there is to it. For one thing, it’s not just Tanqueray vs. Bombay Sapphire anymore. There are a number of new small-batch brands out on the market, many of which are incredibly affordable. And the history of gin is fascinating.

The basics: gin is a spirit made from a mixture of malted grains such as barley, wheat, corn, and rye. It is flavored with herbs, particularly juniper, which gives it its name (the Dutch word for juniper is jenever). Though just about all the gin you probably drink is London Dry Gin, there are actually several different types.

Genever, or Holland Gin, is the ancestor of modern gin, and may date back to the 13th century. It was produced in Belgium and the Netherlands by distilling malt wine, a liquor made from fermenting malted grains. Because the product of this process didn’t taste very good, distillers added sugar and herbs, including juniper berries, to make it palatable. This mixture was originally sold as a medicinal remedy. While there are still several producers in Europe, the only Genever you’re likely to see in the United States is the Dutch brand Bols Genever. I’ve never tasted it, but Roger Kamholtz at The Kitchn’s excellent Nine Bottle Bar series describes Genever as having a “funky, sweet, almost bready character.” Interesting.

Old Tom Gin is the result of Genever being brought to England. It became particularly popular during the early 18th century, when the country heavily taxed imported spirits. Gin became the drink of the poor, made from grains that weren’t good enough for brewing beer. Supposedly a black cat on a sign outside a drinking establishment indicated that gin was served there, thus the nickname “Old Tom.” The spirit was so popular that this period is now known as the Gin Craze.

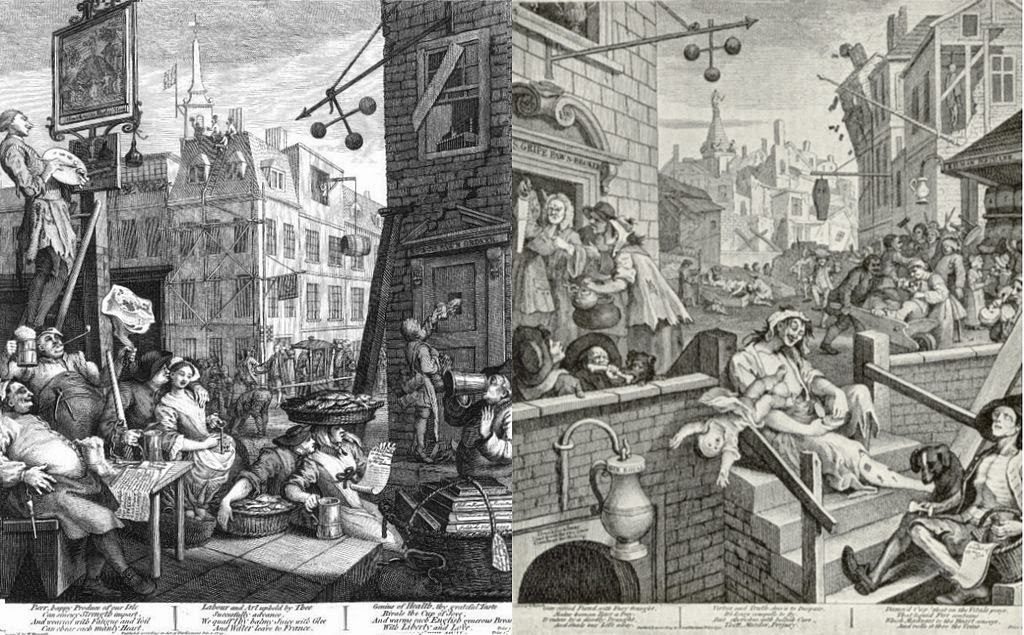

|

| Beer Street and Gin Lane, two prints by William Hogarth, 1751 |

While we now have these back-alley establishments to thank for our Martinis and Negronis, not everyone was so keen on this new spirit at the time. Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe, wrote an essay on this practice in which he declared “that the Liquor call’d Geneva is mortal in it self, and that the Juniper-Berries put into it are Poison.” He argues for the consumption of beer instead, which, unlike Gin, “destroys no Health, wastes no Time, spends no Money, weakens no Understandings.” (I wonder what kind of beer he was drinking.) Propaganda such as the prints above, entitled Beer Street and Gin Lane, discouraged consumption of the much stronger spirit. Guess which print is Gin Lane. Hint: it’s not the one where everybody is fat, happy, and producing great art.

Old Tom is considered the “missing link” between Genever and London Dry Gin. It is intermediate in flavor, not as sweet as Genever or as dry as London Dry. It’s not clear to me at what point Genever became Old Tom in England, but it was likely a gradual evolution of taste. Old Tom in its current formulation was developed in the 19th century. It was extremely popular in the early American cocktail movement, lending its name to the Tom Collins and generally being used where we would use London Dry Gin today. It began to be replaced as a preference for drier cocktails developed. It is, however, experiencing a comeback in the current craft cocktail movement, and you can almost certainly find a bottle at your local liquor store.

London Dry Gin is the gin that you are used to drinking. It was developed in the 19th century along with an improved distillation process that made a much better-tasting spirit that didn’t need sugar to mask its inferior flavor. It remained less popular than Old Tom until the 20th century, when it became the first choice for most cocktails. Its name comes from its birthplace; London Dry does not have to be made in London (and today, most of it isn’t).

Plymouth Gin, on the other hand, specifically refers to gin that is made in Plymouth, England, though it is basically London Dry style. Gin production there goes back to the days of the gin craze. Today there is only one distillery, which produces Plymouth brand.

Sloe Gin is made with a fruit called sloe or blackthorn instead of juniper. Unlike other gins, it is bright red in color. Sloe was common in England during the Gin Craze, and so was used as flavoring. One of the notable cocktails invented with Sloe Gin is the Sloe Gin Fizz. Like Old Tom, it stopped being widely produced in the 20th century, but is experiencing a comeback. Plymouth now makes a Sloe Gin as well as their traditional Plymouth Gin.

On top of all this, there is an emerging category of American Dry Gin that is produced in the US and has less juniper flavor than London Dry; examples include Aviation and Bluecoat.

Individual gins have a lot of variation in flavor due to the different botanicals used to flavor them. Bombay Sapphire, for example, is flavored with almond, lemon peel, licorice, juniper, orris root, angelica, coriander, cassia, cubeb, and grains of paradise, while Hendricks uses yarrow, juniper, elderflower, angelica, orange peel, caraway, coriander, chamomile, cubeb, orris root, and lemon, followed by an infusion of rose and cucumber. These individual flavor profiles mean that certain gins can be better suited for certain cocktails (Hendricks in anything containing cucumber, for example).

Right now the only gin in my bar is a bottle of Tanqueray, but I’m itching to try some others. Ford’s and St. George are currently at the top of my list. What’s your favorite gin?